Hirohiko Araki

Hirohiko Araki (荒木 飛呂彦, Araki Hirohiko) is a mangaka and author of JoJo's Bizarre Adventure, on which this wikia project is based.

Biography

- Hirohiko Araki was born on June 7 1960 in Sendai, Japan.

- Araki left before graduation from Miyagi University of Education.

- Araki is best known for JoJo's Bizarre Adventure, published in Weekly Shonen Jump from 1987 to 2002, before the series transferred to the seinen magazine Ultra Jump in 2004.

- Araki's Buso Poker was a "Selected Work" at the Tezuka Award in 1980.[2]

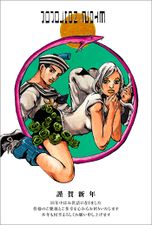

- In 2012, Araki celebrated his 30th year as a manga artist and the 25th anniversary of JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure.

Path to becoming a Manga Artist

The following information was compiled from a lecture Hirohiko Araki gave at Tokai Junior & High School in Nagoya City, Aichi Prefecture, as part of their Saturday Program series, as transcribed/compiled by @JOJO, Japan's premier site for JoJo-related news.

In his youth, Araki lived with his father, an office worker; his mother, a homemaker; and his two younger identical twin sisters.

Growing up, Araki assumed that he lived in a house without any snacks. In reality, his sisters would often eat all the snacks located in the house before he got home from school. Even when there were three snacks, one for each of them, the sisters would usually eat them all and proceed to conceal all evidence of having done so. When these doings came to light, a fight would erupt; and an event of this sort might occur on a daily basis. Araki would often feel such a sense of exclusion and ill-will towards his sisters that at times he felt averse to going home. He used to find relief in spending time alone in his room, reading classic manga from the '70s and his father's collection of art books, which Araki assumes informed his motive for drawing manga.

Araki drew his very first manga while he was in 4th grade. He attended a prep school through junior high and high school, which was where a friend complimented him on a manga he drew for the first time. Araki thought that if his very first fan thought he was good, he might want to become a manga artist. So, he began to draw manga in secret of his parents.

He began submitting work to publishers during his first year of high school; however, all of his submissions were rejected. At the same time, others artists who were around his age continued to make big splashes with their debuts (Ex: Yudetamago, Masakazu Katsura). Araki could not understand why he was being rejected, so he decided to finish off a submission on an all-nighter, go on a 4-hour trip to pay a visit to the editors in Tokyo, and ask them for an explanation.

At first he intended to visit Shogakukan, which published Shonen Sunday, but he was intimidated by the size of their building, and decided to take his submission into the smaller Shueisha (Publishers of Weekly Shonen Jump) building next door. It was noon when he visited, but one rookie editor (about 6'2", or 185cm, tall) happened to be there, so he showed him his work. The editor, after reading the first page, promptly quipped "your white-out's leaked (You haven't fixed it)": he was criticized every time the editor flipped through each page. Araki, exhausted from having been up all night, felt like he was going to pass out. However, after he was finished, he was told that it might be good, and was immediately told to fix it up for the Tezuka Awards in 5 days. That submission was "Buso Poker", which won the runner up prize at the Tezuka Awards.JoJo's Bizarre Adventure

The concept of JoJo originated from Araki's admiration of movie actors at the time of it's creation. As Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger were popular at the time, Araki would often wonder "Who was the strongest person in the world?" Through this type of thinking, themes such as immortality, justice and things that human innately seek were brought up. Araki had also gone on a trip to Italy 2 years prior to the creation of JoJo's Bizarre Adventure, where he had noticed the Italian art's strive for human beauty. Araki incorporated this concept, along with the previously stated themes and the use of "Super Macho Guys" as he puts it, to form the basis around Part I: Phantom Blood.[3]

The story in JoJo is divided between two parallel universes. Beginning in 1987 with Part I: Phantom Blood, the first of these starts within the deceitful relationship between villain Dio Brando, arriving from a poor and abusive background, and hero Jonathan Joestar, son of a benevolent noble. Attrition between Jonathan's descendants and their allies and Dio's subjects and followers provides the main source of continuity in this series, set between 1880 and 2012, in locales spread across England, the U.S., Italy and Japan, primarily. Beginning in 2004 with Part VII: Steel Ball Run, the second universe starts in analogous terms in 1890, in the U.S., and is focused on the quest of Gyro Zeppeli and Johnny Joestar for the acquisition of a certain mystical object, which produces implications that are explored after a leap to the present day in Part VIII: JoJolion, set in Japan.

The body of JoJo includes a variety of tonally distinct episodes and diversions, but the plot is carried by generally dramatic and violent interactions between supernaturally powerful individuals of mutually exclusive ambitions, moral standards or beliefs, and a chase among the emergent heroes of a given story arc to intercept a central antagonist. The series spans a range of genres, including Action, Adventure, Horror, Thriller, Mystery, Supernatural fiction, and Comedy; with recurrent themes including Fate, Fortunity, Justice and Redemption. Many references to modern film, television, fashion, popular music and fine art are readily identifiable throughout JoJo in many settings and the characterization, nomenclature and background of the cast.

The signature mechanic of the series is defined in the first two episodes by the Ripple, wielded in the trained human body, and the supernatural Stand power thereafter. Examples of physical, mathematical and psychological theory, biology, technology, myths, historic events, and natural phenomena inspire and inform the functions of JoJo 's multitude of unique Stands. The series occasionally proposes fanciful developments upon contemporary scientific theory as a platform for the mechanisms by which certain Stands exert their influence on nature.

Morioh, fictional Japanese town and base of Part IV: Diamond is Unbreakable and as a distinct incarnation in the ongoing Part VIII: JoJolion tends to take a more culturally detailed description and both reference and serve more contemporary topics (such as the 2011 Tohoku earthquake) than settings in other episodes of JoJo; and so would seem to represent Araki's own localities. Stand-wielding mangaka Rohan Kishibe, a resident of Morioh introduced in Diamond is Unbreakable and guide in a handful of JoJo spin-offs, stands as a mild parodical self-insert.

Style and Influences

A consistent element of Araki's drawing is a highly dynamic treatment of the picture plane, to which everything including anatomy, perspective, scale and range is subject.

In terms of cartooning, a comparison can be drawn between Phantom Blood, Battle Tendency and Stardust Crusaders (1987 - '92) and the hypermasculine anatomical ideals applied by Tetsuo Hara in Fist of the North Star, and referenced by Araki in relation to action heroes of the 1980s.[3] Diamond is Unbreakable ('92 - '96) marks a transition to a more intersexual model. Steel Ball Run (2004 - '11) sees greater realism, along with further integration of ideals of beauty consistent with the mode in fashion design.

Araki has named Paul Gauguin and his approach to color theory as an influence, and has indicated admiration for Leonardo da Vinci in JoJo through the voice of some characters, recurring images authored by da Vinci, and his association with such key concepts as the golden ratio (or golden rectangle). Araki is also seen making reference to a book of Michelangelo's work[4] in the construction of a 2013 piece.[citation needed]

Manga that Araki has named as admirable or having had particular influence on him include Ai to Makoto by Ikki Kajiwara and Takumi Nagayasu, the most significant of his youth;[5] Ore wa Teppei by Tetsuya Chiba, which inspired him while in middle school to join the kendo club;[5] and Babel II by Mitsuteru Yokoyama, particularly influential for the concept of combat defined by special rules or laws.[3]

Publication

Many of Araki's creations including JoJo's Bizarre Adventure have been translated and released in Europe, but so far only JoJo and Baoh have been released in the U.S., one theory being that Araki's frequent references to Western music, film and others would represent a violation of U.S. intellectual property law. Publications by Viz Media replace certain references within the copy of the manga with thematically comparable alternatives. The American localization of Capcom's fighting games based on JoJo follow the same procedure.

Works

- Buso Poker (1980)

- Outlaw Man (1982)

- Virginia ni Yohroshiku (1982)

- Magic Boy B.T. (魔少年ビーティー mashōnen bītī 1982–1983)

- Baoh (1984–1985)

- Gorgeous Irene (1985–1986)

- JoJo's Bizarre Adventure (1987—current)

- Part I: Phantom Blood (1987-1988)

- Part II: Battle Tendency (1988-1989)

- Part III: Stardust Crusaders (1989-1992)

- Part IV: Diamond is Unbreakable (1992-1996)

- Part V: Vento Aureo (1996-1999)

- Part VI: Stone Ocean (2000-2003)

- Part VII: Steel Ball Run (2004-2011)

- Part VIII: Jojolion (2011-current)

- JoJo 6251 (1993) (Artbook)

- Under Execution, Under Jailbreak (Collection) (1999)

- JOJO A-GO!GO! (2000) (Artbook)

- The Lives of Eccentrics (1988-2004)

- Thus Spoke Rohan Kishibe - Mutsukabezaka (2006)

- Front cover of Cell (scientific journal) (September 7, 2007)

- Rohan at the Louvre (2010)

- Rohan Kishibe Goes to Gucci (2011)

- Thus Spoke Rohan Kishibe - Episode 5: Village of Millionaires (2012)

References

- ↑ Interview with Shoko Nakagawa, 2007

- ↑ Tokai High School lecture 2006, part 1

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Phantom Blood PS2 release interview, 2006

- ↑ Michelangelo – Tuttle le Opere – Edizione Riserveta ai Musei e Gallerie Pontificie, ISBN 9788872040256

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Tokai High School lecture 2006, part 3

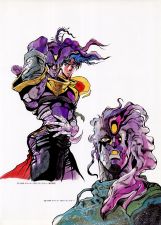

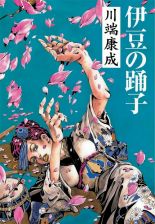

Gallery

External links

Tokai High School lecture, 2006, translated by Neuroretardant for ComiPress